This goes back to the style of 105 Things About Me -- a self-indulgent look at, well, myself. Not quite myself -- but instead at one of the best ways I've ever found of getting a look at a person from the outside: the books I read. It is, then, half self-indulgence and half suggested reading.

I used to listen to a radio station that played the seminal "Desert Island Discs" program. Well known (or as the show wore on, progressively less well known) artists would list the ten disks that they would, if trapped on a desert island, want to have with them. I don't listen to all that much music, and my tastes are with little exception confined to relatively mainstream singer-songwriter stuff.

If trapped on a desert island, then, what ten books would I take? I'll admit to a certain degree of practicality: I've opted for long books and books with a high "contemplation" value. I've kept in mind the idea that this reading list will potentially have to tide me over for a while and have included a bit of variety even if that action meant I'd have to leave a couple of strong favorites at home. There are, however, a couple of emotional inclusions, books in there because they should be or because I know they bring me an odd sort of comfort.

I'd also like to apologize to the people at Amazon.com for, in some cases, borrowing their cover art in order to make this article have some visual appeal. For what its worth, those pictures all link back to Amazon if you are interested in exploring one of the titles a little further.

Neuromancer

You knew this would be in here. This is, without a doubt,

my book. It is the book I take with on airplanes, read about every year just to keep in touch, write essays about when I can't think of anything else. It is the drug soaked future vision of techno-hippie-curmugeon William Gibson. As the product of a man with more experience with psychedelics than CPUs, it is in many ways a shockingly prophetic vision of the future. Granted, the Rise of the East that so dominated future visions of that era (anyone remember Crichton's hideous

Rising Sun?) has generally failed to come to pass. Neither did World War Three. Nor did the space colonies, for that matter.

But what makes

Neuromancer interesting as a work of vision are the computers. Artificial intelligences and neural connections may still be the stuff of sci-fi dreams, but Gibson saw perhaps more dramatically than anyone the rise of

pervasive computing and connectivity. While everyone else was preoccupied with hard science fiction -- precisely understanding how the things o their future would work -- Gibson ignored the details and painted with his broad noir brush strokes. As a result, he was one of the few to look far enough ahead to see what would come to pass in a few decades. Granted, there are anachronisms such as the bank of pay phones that are essential to the book's most creepy moment or the non-standard multi-pin connectors that briefly frustrate Case just shy of the climax. But overall Gibson offers no clue as to how things work (how exactly are Molly and Case able to stay in touch during the Straylight run, for example?), but just lets them happen. And as a result, he saw (in some senses quite literally) the future in a way few others ever did.

The writing is as dark and imagistic as is the universe. The crumbling derelicts of Western Civilization are described not through sweeping panoramas but through isolated, vivid scenes. Sometimes the prose rambles on -- particularly towards the end, during the

2001: A Space Odyssey-like descriptions of Case's final hallucinatory flight through the joint defenses of the Wintermute and Neuromancer AI's. As I said, sometimes I think Gibson really did

see his future...

The Diamond Age

A stark contrast from Gibson's seat-of-the-plants imagination,

The Diamond Age is a product of the methodical, well informed, and carefully considered work of Neal Stephenson. Here is a future cast deep into a vision of nanotechnology and digital divide. In many ways it is starkly different from Gibsons -- certainly much more of a post-Cold War work, steeped more in Huntington than in Reagan. Where

Neuromancer presents it's future with a damn-the-details disregard for implementation and infrastructure,

Diamond Age very nearly presents a complete course in the ideas of Alan Turing. Indeed, some of the book's most charming passages are those excerpts from the

Primer devoted to Nell's technological education (I've actually done "

Primer only" readings of the book -- skipping the mainline action in favor of that belonging to Princess Nell.

It is a much more hopeful book that

Neuromancer, even though the social and technological divide is, if anything, more dramatic than in the earlier book. Whereas

Neuromancer presented an undeniably

dark vision of humanity,

Diamond Age somehow shows a future where, while there may be crime and corruption and war and poverty, and while the seemingly limitless power of nanotechnology has failed to fulfill more than a fraction of its promise (at least for most of the world!), the better angels of our nature still seem to have a fighting chance and the reader is left believing in heroes (and even more so in heroines, since Stephenson is just about the most feminist of science fiction authors).

Granted, the book does occasionally suffer from logical inconsistencies, but I am willing to put this off to my incomplete understanding of the world (one could, for example, look at an incomplete narrative of events in our world and wonder why some people have amazing handled directions that instantly supply them with directions to any point on Earth...and others don't). The book (and Stephenson's work in general) has also been widely criticized for its abrupt ending. I agree -- it sometimes feels as if Stephenson felt like "alright, I'm done here, let's get this thing wrapped up" and pushed the pace in the final few dozen pages. But the fact is, the events of those pages are told with what I think is a deliberately synopsizing style. We know the characters, we know the action. In a sense, the main stories have ended. The last chapter (or two) is more like those wrap-up title cards that used to be popular in movies (and still are for docudramas) which tell the audience what characters went on to do hard time and what characters went on to found successful aerospace firms. I'm picturing the end of HBO's superlative rendition of

Band of Brothers, by the way, where just about everyone ended up doing something amazing -- except for Dick Winters who I guess pretty much returned to farming and then quietly retired and I vaguely believe may not live too far from here. So if you view it as a wrap up, of a realization that the story is over, we're just tying off a few loose ends -- and that the story

isn't over -- then it feels a lot better.

I also recommend the audiobook, superbly read by Jennifer Wiltsie (incidentally that controvertial ending flows very nicely in her reading). The voice is primarily that of Princess Nell, though the characterizations are all superbly done without any of the drama or histrionic over-acting that some readers seem compelled to include.

The Name of the Rose

Those of you who know me

knew this was going to be here. It has to be, after all. It is the only medieval (I hope I spelled that right) mystery about codebreaking written by a semiotics professor I know of. It is also without a doubt the peak of Umberto Eco's willfully obtuse and esoteric writing. The very conceit of the book -- that it is a translated reconstruction of a manuscript written by a dying monk hundreds of years ago -- is pure Eco. And with his absurd range of knowledge (and feel for the styles of that age), he pulls the trick off as convincingly as Rob Reiner and Christopher Guest do in

This is Spinal Tap (which is a great deal funnier, by the way).

The Name of the Rose is a book to submit to. Before picking it up (and periodically during the reading process, whenever one of Eco's page long comma-laden sentences threatens to drive you to drink) repeat this special variation on the serenity prayer to yourself:

Grant me the intelligence to understand the parts that can be understood.

Grant me the patience to make it through the parts that cannot be understood.

And the wonderment to enjoy it all anyway.

(And, if necessary, go ahead and drink)

Once you decide to take this ride, it is a little bit like a hiking trip through a strange and exotic land (right now, Erica is reading a book about someone's adventure of just this sort in China). There will be times you have no idea what is going on, but eventually frantic hand-waving will help you find the bathroom or the teahouse or the place you can buy DVD's really cheap. There will be times you are lost, confused, and worried the train that just left was the last one out for the winter. There will be times you will follow a group of people who look similar to you (and therefore must know what is going on) only to discover they are from the Ukraine and are also lost. But in the end, the trip and its memories will be an amazing collection of thoughts and experiences so rich that they have to lie in your head for months or years -- and be revisited through photographs, storytelling, and dreams -- before they form a coherent picture and their full impact is felt.

This is how

The Name of the Rose feels. It is a trip back to a time so different from our own that it is, in many ways, nearly incomprehensible. An Italian monastery during the time of the Papal Schism, as seen by a young boy apprenticed to a mysterious (and intentionally Sherlock-Holmes-like) monk. A mystery that explores murders that weave the most base of human desires with the most erudite. A code that, while ultimately not-so-difficult, forms one of the diverse hearts of the story. And everywhere, the complex and layered symbolism not just of Eco's own mind but that which permeated the 14th century itself. Roll with those overly-long descriptions and witch off the hyper-paced superficiality of the modern age, when beauty is just beauty and function just function. Instead get yourself thinking about the symbolism that is inherent in any object (and I take a broad definition of object, essentially using it as a postmodernist would use

text). Today, we rarely plan symbolism, it tends to just happen as a side effect of more banal choices. Back then, it was the essential and driving design consideration.

Smiley's People

Welcome to the 20th century. The year is, well, sometime in the late 1970's (the book was written in 1979). The cold war is at its peak, rising to a final dramatic crescendo that, though no one knows it, will suddenly flare into stillness and the end of that movement of the symphony of history. The spy game is the sweaty place of men working alone, relying on cool wit and awareness. The men who were honed in the tumult of the Second World War are now at that time in their lives when they are either pensioned retirees or string-pulling masters. John Le Carre wraps up a long and wonderful thread of two such men -- George Smiley and his Soviet foe Karla -- in a book that is, I believe, the single finest piece of spy fiction ever written.

If you are thinking of picking it up, don't worry that you need to go back and pick up the two other books of the "main" Smiley/Karla trilogy (or the two prelude books that introduce Smiley or any of the other books in which me makes bit or major appearances).

Smiley's People stands on its own as a single and wonderful work. I actually consider it to be significantly superior to any of the other Smiley books, to be honest. One of the joys of the book

is the reunion value. To put it in a nutshell (I've deliberately avoided plot summaries here, but need to do a little one for this to make sense), retired and somewhat defeated British spymaster George Smiley is dragged out of his somewhat head-in-the-sand retirement for one final battle against his seemingly victorious rival from the Soviet Union (that's why I avoid plot summaries -- they always sound like that "back of the book" prose). Along the way, Smiley brings together an entire cast of characters from the old books, from the obvious (Toby Esterhase) to the obscure (Inspector Mendel). The result is a book that resonates with a "let's see what this old girl still has in her" sort of drama that I'm an admitted sucker for. It's part of what makes some of the Star Trek franchise so appealing (the Enterprise speeding away from the sabotaged Excelsior, for example, or the refitted Enterprise coming to the rescue in that glorious final episode of TNG,

All Good Things). But you needn't actually know those stories to appreciate this aspect of the book. Indeed, I read them out of sequence since, when I picked each of them up, I had no idea the book was part of a larger whole.

Narratively, Le Carre does one of the most masterful jobs of perspective management that I have ever seen. He shifts his focus from that of a marginally omniscient narrator to an internal monologue from a mentally troubled Russian girl with such grace that the dramatic changes in tone are entirely seamless. Some of the book has a delightful dramatic irony, where the narrator almost seems to be the author of an official Circus history looking back on the event with the perspective of months or years, breaking aside for discussions of events taking place

after the conclusion of the mainline story and limited in knowledge by official records. At times the narrator seems to know Smiley's deepest thoughts and musings, but at times those same thoughts are protected and only accessible through observation and speculation. Throughout runs a dry and very English wit, the wry observations of a narrator as world-weary and cynically perspicacious as is his protagonist. The result is one of the most unique and entertaining narratives I have ever read. I suspect a purist would complain that it was gimmicky, inconsistent, and unprofessional. But I am not a purist and enjoy a good story, well told, by any appropriate means.

The moments when the book does give is a look into Smiley's mind are a fantastic look into the mind of a man with (to use the book's own phrase), "many heads under his hat": retiring academic, veteran spy, civil servant, conscientious leader, failed husband, defeated warrior, and finally and most tellingly, a man who is in a position after years of frustration, failure, and inadequacy to finally gain the upper hand over his foe.

The Lord of the Rings

There are, in sports such as diving and gymnastics, certain obligatory moves that must be displayed during a competition or a routine. And, for some people, there are certain obligatory books that must be put on lists such as this one.

Lord of the Rings is one of those. If I didn't include it, I'd have to hand in my Science Fiction & Fantasy Fan card and walk away in shame. But the thing is, it

is a good inclusion. I've never been quite the fan that some become. I never tried to make my own dictionary of the Elvish language or write a fanfic (footnote: the spell checker on my blogging software, presumably the one built into OS-X 10.5, knows the word "fanfic." Tells you something, doesn't it?) or draw maps of Middle Earth. But I'm not necessarily given to such acts of devotion.

But for richness of world, complexity of narrative, and degree of unspoken backstory, it is hard to beat Tolkien. One of the things that really does make all of his work so enjoyable is the feeling that it isn't a work of fiction, but a work of history. And just as even the most thorough of historic works can touch only a fraction of what went on (be it in a day or a few hundred years),

The Lord of the Rings clearly touches only a fraction of what went on during those final days before the fall of Sauron. Tolkien's vast and very English scholars mind created a depth of detail that one can revel in.

It is also the wellspring of all other "quest" books. The fellowship gathers, embarks, divides, divides again, bifurcating into multiple anfractuous plot lines. Indeed, after

Fellowship of the Ring it is entirely possible to read LotR (I just did it, I used the fanboy shorthand, sorry) as several concurrent novels, picking and choosing story lines. "Hm...today I think I will read just the story of Pippen..." But, gloriously, everything comes together at the end as, through nearly independent action (or the smooth hand of fate) the principles come back together, one at a time, until the final tearful reunion.

The dialogue may, at times, be heavy handed. I find Tolien's insistence on those interminable songs profoundly irritating (granted, he's trying to build a viking-like character, but this didn't need to turn so Wagnerian!). Sometimes the exclusion of backstory can leave the new reader staggering along for a few dozen or a few hundred pages (but you always know that exclusion is deliberate and not the product of the author not

knowing what happened outside the story). The number of named characters defies counting, and little guidance is initially provided as to the potential importance of a newcomer.

But for all that, for all of the flaws it

does possess, the work is a true epic. Sweeping, grand, and beautiful in scope.

The Codebreakers

Somewhat tongue-in-cheekishly, I credit this book with my marriage to Erica. To give it full credit is obviously absurd, my willingness to eat the deep fried shrimp heads clearly counted for something. But despite later culinary adventures, our shared ownership of this book was one of the first "hey, this guy/gal looks interesting!" moments. At least we knew we'd have

one thing to talk about on a date.

Simply put,

The Codebreakersis a seminal work that has yet to be even remotely equaled. It is, without a doubt, the best single volume telling of the history of code-making and code-breaking up through the first third of the 20th century. Later than that and it starts to run into the constraints of secrecy -- the Enigma decrypts of the Second World War weren't made public until several years after its first publication -- and of a slapdash effort by Kahn to update the text with such modern technologies as the DES standard. But he is out of his element here, and that's why

Applied Cryptography is on the list in any case. For the eras when ciphers were produced by men laboring with pencils, paper, typewriters, and perhaps primitive collections of wheels and rods (he does a decent job with technology up to about the Hagelin machines), for the era when the field was more intuition and art than the rigorous solving of equations that XXXX turned it into, this is simply

the text.

As many historians do, Kahn does sometimes write for his time, implying that the reader should have familiarity with events and people now rendered obscure by the three and a half decades since the text was produced. There is also a definite conservatism in the work, something that the eccentric nature of those drawn to cryptography inescapably draws out. But for telling the human tale of an intensely technical field, Khan's book is without equal (just ignore the moments when his reporting turns to judging). To hear how Georges Painvin broke ADGVX through a single immense act of will, loosing a dozen or more pounds in the process,

The Codebreakers is the book. To hear about eccentric Victorian gentlemen-scholars inventing cipher systems between dabbling in natural philosophy and at attending hunts, it is the book.

A Distant Mirror

You're probably starting to realize how much I enjoy history. I read, at least partially, for a sense of escape. I want to get away from my corporate day job where people feel the need to invent replacements for perfectly good words (e.g. saying "we'll go ahead of the ask succeeds and we get funding" rather than the perfectly good and well seasoned word

request). But I digress. No world is more bizarre and alien than the 14th century. And given that I just pushed through a few science fiction novels, that is saying something!

In all seriousness, Tuchtman writes a great history here. It is a history of a time so distant in time and values that it really does feel, at some times,

alien. She brilliantly structures the work around the armature of a single man's life, using this structure to organize the background and the primary narrative. Instead of

only giving us the distant, dispassionate perspective of typical histories, she illustrated the sweep of the times through what is essentially a massive and recursive work of biography, always sweeping aside to cover a tangent and then flying back to the main story, grounding the dramatic events of that age in the life of a single blading man.

And what a collection of events the 14th century provides us with. I've already talked about

A Distant Mirror in regards to its totemistic value as a perspective provider ("It can't be that bad...") whenever the nightly news gets a little depressing. And it was indeed a motivation similar to this that inspired Ms. Tuchtman to write the book. But here, in one book, we have the papal schism, the black death, and the hundred years war. It is enough tumult to satisfy a millennium's worth of tragedy, all packed into a hundred years. Given the drama (and most of it bad) contained in this history, it could easily turn maudlin and depressing. But the pervasive perspective is the ability of humanity to adapt and survive. It is, as such, a profoundly motivating and reassuring book, in addition to being densely informative.

The Fabric of the Cosmos

One day, before I die, I would like to understand

everything in this book. I suspect that, when that happens, I will quietly dissolve into a vaporous cloud of disassociating particles. Fortunately, it will take quite a long time for that to occur.

Brian Greene, everyone's favorite vegetarian string theorist, tackles not his particular specialty (and despite Roger Penrose's characterization of him as a hedgehog, Greene certainly knows enough of a breadth of physics to pull this off) but rather the entire scope and wonder of the leading edge of physical understanding. Several ingredients contribute to ming

Fabric of the Cosmos so wonderful to read. Greene's brilliant analogies (usually involving The Simpsons) not only clarify concepts but are amusing in their own right (the whole book has a dry and subtle wit). The physics discussed is profoundly interesting, even disturbing if you don't accept the idea that our reality may well be quite a bit more subtle and bizarre than generally expected. But finally, and perhaps most significantly, is Greene's own fascination with the material he is coming. The book brims with his own energy and enthusiasm, sense of wonder and amazement. In many ways, despite the enormity of the material covered, the book is very personal, opening as it does with an anecdote from the author's childhood and moving on to discuss the very researches that fill his day job (and what a day job) at Columbia University. This comes through most clearly in the final chapters when Greene quite admittedly takes the current state of the known and speculative art and plunges headlong into the visionary realms of where this knowledge could take us.

The entire book is set as a wide-ranging tour, a grand sweep across the most fundamental infrastructure of the universe. The big bang, inflation, the kinky activities inside the Planck limit, the quantum and the Einsteinean, all get some time. Unlike

The Elegant Universe, Greene's first book, this is not an evangelism of String Theory. Obviously this approach to answering the fundamental questions and contradictions that currently arise in physics figures prominently, being Greene's area of research and specialization. But the book only graces this area when appropriate and necessary. I actually wish that it spent more time here -- I truly

like the ideas of String Theory (as much as it might currently be caught in a physical backlash), but can always pick up the adjacent and equally well thumbed copy of

Elegant Universe when I need to.

On Food and Cooking

What could be better than a book that is simultaneously about science

and cooking? Very few things, I tell you that, when the book has the lucid explanations, beautiful production, and sweeping scope of

On Food and Cooking. As an aside, you many have noticed just how often the word

sweeping shows up as a word of praise in this entry (at least I think it does!). I tend to like my non-fiction that way: broad, epic, profound. I'm a generalist, I suspect, and like situations that let me see as broad a scope as possible. I also relish the moment of connection when seemingly disparate threads merge into a single coherent story.

Part of the appeal of

On Food and Cooking is its fearless willingness to actually tackle some organic chemistry. I've often characterized this branch of the sciences as the one that I simply don't get. And it is true. Those who understand it tell me its easy, I just need to memorize few things. I think they possess some strange gift. Organic chem (or "Orgo") isn't like, say, the way-out-there physics of

The Fabric of the Cosmos. That's like reading a complicated story that is in a language you know. Organic chemistry is like reading a complicated story in a language you've never seen before. For me at least! McGee manages to tackle the fundamentals of orgo pretty clearly -- probably partially because he has a clearly defined upper bound of complexity and partially because the topic he's working with (food) is more motivating than that of most organic chemistry texts. The explanations are also lucid and engaging, trust me, so it is not entirely the appeal of the topic that is at hand.

But beyond the orgo, this is a book about food, abut how food happens, about what food does, and about why all of these things happen. The popularization of food science owes a lot to Alton Brown, The Food Network's geek-cook extraordinaire (though I will say that I've liked Alton's shows less and less -- as he seems to rebrand from a geek into more of a welding-glove-wearing-man's-man-chef character). Now it doesn't take much exploration to realize that Alton learned everything he knows about food science from periodic guest Shirley Corriher and her fantastic book

CookWise. This book is, in its own turn, a more conversational and applied version of

On Food and Cooking. I've obviously chosen to go straight to the most pure source I know, skipping the intermediates.

On Food and Cooking is as endlessly interesting (and entertaining) as is the world's unending variety of food.

Applied Cryptography

I keep trying to replace

Applied Cryptography in my collection. It is, after all, more than a decade old in a field that has seen shockingly rapid advancement in that time. Most of the algorithms discussed in the book are obsolescent in today's security world. Perhaps even more critically, an awareness of system design now permeates security thinking, and not just a building-block approach. But nothing, and I mean

nothing that has come out since 2001 has offered more than the slimmest threat to Schnier's classic.

Practical Cryptography comes close, really close. And, if a second edition were to come out that updated

it to include the latest and greatest, it would stand a real shot at taking the crown of Modern Cryptography Book On Nick's Island.

But enough about its superficial obsolescence, what has

Applied Cryptography done so well that it still shows up on the list? The answer is that, like no other book on the topic, it builds an actual understanding of how the processes of security work. It contains

both the mathematical rigor required to construct (or deconstruct) a security system and even more profoundly an ability to explain...to

clarify...how these mathematical components operate. It takes the time to step, conceptually, through the now iconic cases of Alice, Bob, Mallory, and the various other characters of Schnier's explanations. It backs these cases up with some of the underlying constructs and mathematics. The recently maligned weak point is that the focus is on explaining individual systems and not on overall processes -- but as someone who does not intend to actually design a cryotpsystem, the clarity of these explanations makes their omissions entirely forgivable.

Much of the content, then, is timeless. Most of the great message passing schemes remain unchanged, or at least still valid. The ciphers discussed may not be fighting in the front lines anymore, but that does not make them unworthy of study. The knowledge in this book has not been replaced, merely supplemented. Now if I were heading off to a desert island, I'd like to take my copy with me just as it is -- broken spine and all -- for the sake of the half dozen printouts I've stuck in between various pages, updating the content with some current state-of-the-art examples of cipher algorithm design. Let me stick in a few sheets of paper and, no reservations at all,

Applied Cryptography will beat all comers, hands down and no reservations: Rijndael/AES, of course, the flawed but endemic mobile communications ciphers of A5/1, E0, and KASUMI, the fascinating but flawed Roo/Py and Phelix, the phenomenal elegance of Trivium and Grain, and the enigmatic Don Coppersmith's suspiciously rotor-like Scream. That's nine ciphers...might as well make it ten and throw in Camellia for a look at Japan's stylings in the area.

But this is the sort of book that

should have a busted spine, dog-eared pages, notes and highlights, and random pieces of paper sticking out of it. In the way that comic book readers show their love in a carefully bagged-and-boarded book, readers of

Applied Cryptography should show their love love in a manner more akin to that scene in the sauce stained, water wrinkled, footnoted pages of cook books.

What, in my roundabout way, I am trying to get to is this: I love sitting on a barstool, at a bar, watching the world go by (or participating in it -- barstool does not mandate or even imply passivity). The personal geography of the stool and the bartop are nearly perfect. A great height (if it is not too tall) for working on laptop. A great height for a book or magazine or some old fashioned pen-and-ink notepaper. There is enough space to spread out -- but not so much as to enable uncontrolled sprawling. A plate, a drink, and a book/laptop/magazine fit perfectly. This forces a tidy work habit and the selection of essential resources. The height of the surface also enables a pleasant multitasking -- the sharing of time between food and drink and whatever form of work (or recreation -- for a laptop computer or a book or some notepaper could imply either for me) is at hand.

What, in my roundabout way, I am trying to get to is this: I love sitting on a barstool, at a bar, watching the world go by (or participating in it -- barstool does not mandate or even imply passivity). The personal geography of the stool and the bartop are nearly perfect. A great height (if it is not too tall) for working on laptop. A great height for a book or magazine or some old fashioned pen-and-ink notepaper. There is enough space to spread out -- but not so much as to enable uncontrolled sprawling. A plate, a drink, and a book/laptop/magazine fit perfectly. This forces a tidy work habit and the selection of essential resources. The height of the surface also enables a pleasant multitasking -- the sharing of time between food and drink and whatever form of work (or recreation -- for a laptop computer or a book or some notepaper could imply either for me) is at hand. But almost all of this could happen at a table. The relationship between the tabletop and the body is not too different from that between the bartop and the body. But it is a significant difference. The bartop encourages a leaning, relaxed, elbows-on-the-table mood. The table is a rigorous place, both by arrangement and psychology, where posture must be maintained, children should be seen but not heard, and knife and fork must be used properly.

But almost all of this could happen at a table. The relationship between the tabletop and the body is not too different from that between the bartop and the body. But it is a significant difference. The bartop encourages a leaning, relaxed, elbows-on-the-table mood. The table is a rigorous place, both by arrangement and psychology, where posture must be maintained, children should be seen but not heard, and knife and fork must be used properly. And here, for the first time, we will also encounter the alcohol. From ancient Sumer on, people have found that properly treated fermented grains can produce a relaxed state, inducing of creativity, conversation, risk taking, and even, in the right situations, considerable productivity. In the classic pattern of the "if you mean whisky" fallacy, it can also produce excessively abrupt emails, poor proofreading, a tendency for summary resignations, misuse of Britney Spears crotch shots in PowerPoint presentations, and worst of all corporate Karaoke. But a little self restraint, here, and the benefits out weigh the risk of accidentally showing board members a photograph of Brit's underwear.

And here, for the first time, we will also encounter the alcohol. From ancient Sumer on, people have found that properly treated fermented grains can produce a relaxed state, inducing of creativity, conversation, risk taking, and even, in the right situations, considerable productivity. In the classic pattern of the "if you mean whisky" fallacy, it can also produce excessively abrupt emails, poor proofreading, a tendency for summary resignations, misuse of Britney Spears crotch shots in PowerPoint presentations, and worst of all corporate Karaoke. But a little self restraint, here, and the benefits out weigh the risk of accidentally showing board members a photograph of Brit's underwear. And then finally there has been the slow, bitter meltdown of Eclipse Aviation. At some point, I stopped believing and saw this as something that was bound to come. But not always. Five years ago, Vern's promises sounded good. Revolutionary, almost. A personal jet, a family flivver of the air. At long last Lewis Black and I would have our flying cars.

And then finally there has been the slow, bitter meltdown of Eclipse Aviation. At some point, I stopped believing and saw this as something that was bound to come. But not always. Five years ago, Vern's promises sounded good. Revolutionary, almost. A personal jet, a family flivver of the air. At long last Lewis Black and I would have our flying cars. And now back to Eclipse (and perhaps Space-X). Where is the flaw? Business plan? Technology? Both? Neither? I lean to both -- a technological product that was designed with enough giddy naivety as to be brittle and intolerant of setback and failure -- the failure of the FJ22 and the original avionics system -- and enough cut corners as to generate problems once in service. A business plan that depended on successes in volume production and demand generation that have, so far, eluded them. Eclipse isn't the first to fall to this error -- of assuming or expecting a demand that fails to appear. McDonnell (now Boeing) made the same sad error in planning the Delta IV rocket. Externally a beautiful vehicle, the Delta's approach to cost-effective launch pricing was based around generating a large demand and benefitting from economies of scale in production and launch. For various unfortunate reasons, this failed to appear.

And now back to Eclipse (and perhaps Space-X). Where is the flaw? Business plan? Technology? Both? Neither? I lean to both -- a technological product that was designed with enough giddy naivety as to be brittle and intolerant of setback and failure -- the failure of the FJ22 and the original avionics system -- and enough cut corners as to generate problems once in service. A business plan that depended on successes in volume production and demand generation that have, so far, eluded them. Eclipse isn't the first to fall to this error -- of assuming or expecting a demand that fails to appear. McDonnell (now Boeing) made the same sad error in planning the Delta IV rocket. Externally a beautiful vehicle, the Delta's approach to cost-effective launch pricing was based around generating a large demand and benefitting from economies of scale in production and launch. For various unfortunate reasons, this failed to appear. Cirrus is out there, with a successful line of piston singles and a sexy little jet on the drawing board. Cessna's managed to keep true to their word and move from strength to strength -- including the wonderful little Mustang that just might have contributed more than a little to Eclipse's troubles. Orbital is building a larger-yet rocket from their well understood and consolidated base. So the startups can continue and grow secure. The big guys can show some flexibility and innovation.

Cirrus is out there, with a successful line of piston singles and a sexy little jet on the drawing board. Cessna's managed to keep true to their word and move from strength to strength -- including the wonderful little Mustang that just might have contributed more than a little to Eclipse's troubles. Orbital is building a larger-yet rocket from their well understood and consolidated base. So the startups can continue and grow secure. The big guys can show some flexibility and innovation. You knew this would be in here. This is, without a doubt, my book. It is the book I take with on airplanes, read about every year just to keep in touch, write essays about when I can't think of anything else. It is the drug soaked future vision of techno-hippie-curmugeon William Gibson. As the product of a man with more experience with psychedelics than CPUs, it is in many ways a shockingly prophetic vision of the future. Granted, the Rise of the East that so dominated future visions of that era (anyone remember Crichton's hideous Rising Sun?) has generally failed to come to pass. Neither did World War Three. Nor did the space colonies, for that matter.

You knew this would be in here. This is, without a doubt, my book. It is the book I take with on airplanes, read about every year just to keep in touch, write essays about when I can't think of anything else. It is the drug soaked future vision of techno-hippie-curmugeon William Gibson. As the product of a man with more experience with psychedelics than CPUs, it is in many ways a shockingly prophetic vision of the future. Granted, the Rise of the East that so dominated future visions of that era (anyone remember Crichton's hideous Rising Sun?) has generally failed to come to pass. Neither did World War Three. Nor did the space colonies, for that matter. A stark contrast from Gibson's seat-of-the-plants imagination, The Diamond Age is a product of the methodical, well informed, and carefully considered work of Neal Stephenson. Here is a future cast deep into a vision of nanotechnology and digital divide. In many ways it is starkly different from Gibsons -- certainly much more of a post-Cold War work, steeped more in Huntington than in Reagan. Where Neuromancer presents it's future with a damn-the-details disregard for implementation and infrastructure, Diamond Age very nearly presents a complete course in the ideas of Alan Turing. Indeed, some of the book's most charming passages are those excerpts from the Primer devoted to Nell's technological education (I've actually done "Primer only" readings of the book -- skipping the mainline action in favor of that belonging to Princess Nell.

A stark contrast from Gibson's seat-of-the-plants imagination, The Diamond Age is a product of the methodical, well informed, and carefully considered work of Neal Stephenson. Here is a future cast deep into a vision of nanotechnology and digital divide. In many ways it is starkly different from Gibsons -- certainly much more of a post-Cold War work, steeped more in Huntington than in Reagan. Where Neuromancer presents it's future with a damn-the-details disregard for implementation and infrastructure, Diamond Age very nearly presents a complete course in the ideas of Alan Turing. Indeed, some of the book's most charming passages are those excerpts from the Primer devoted to Nell's technological education (I've actually done "Primer only" readings of the book -- skipping the mainline action in favor of that belonging to Princess Nell. Those of you who know me knew this was going to be here. It has to be, after all. It is the only medieval (I hope I spelled that right) mystery about codebreaking written by a semiotics professor I know of. It is also without a doubt the peak of Umberto Eco's willfully obtuse and esoteric writing. The very conceit of the book -- that it is a translated reconstruction of a manuscript written by a dying monk hundreds of years ago -- is pure Eco. And with his absurd range of knowledge (and feel for the styles of that age), he pulls the trick off as convincingly as Rob Reiner and Christopher Guest do in This is Spinal Tap (which is a great deal funnier, by the way).

Those of you who know me knew this was going to be here. It has to be, after all. It is the only medieval (I hope I spelled that right) mystery about codebreaking written by a semiotics professor I know of. It is also without a doubt the peak of Umberto Eco's willfully obtuse and esoteric writing. The very conceit of the book -- that it is a translated reconstruction of a manuscript written by a dying monk hundreds of years ago -- is pure Eco. And with his absurd range of knowledge (and feel for the styles of that age), he pulls the trick off as convincingly as Rob Reiner and Christopher Guest do in This is Spinal Tap (which is a great deal funnier, by the way). Welcome to the 20th century. The year is, well, sometime in the late 1970's (the book was written in 1979). The cold war is at its peak, rising to a final dramatic crescendo that, though no one knows it, will suddenly flare into stillness and the end of that movement of the symphony of history. The spy game is the sweaty place of men working alone, relying on cool wit and awareness. The men who were honed in the tumult of the Second World War are now at that time in their lives when they are either pensioned retirees or string-pulling masters. John Le Carre wraps up a long and wonderful thread of two such men -- George Smiley and his Soviet foe Karla -- in a book that is, I believe, the single finest piece of spy fiction ever written.

Welcome to the 20th century. The year is, well, sometime in the late 1970's (the book was written in 1979). The cold war is at its peak, rising to a final dramatic crescendo that, though no one knows it, will suddenly flare into stillness and the end of that movement of the symphony of history. The spy game is the sweaty place of men working alone, relying on cool wit and awareness. The men who were honed in the tumult of the Second World War are now at that time in their lives when they are either pensioned retirees or string-pulling masters. John Le Carre wraps up a long and wonderful thread of two such men -- George Smiley and his Soviet foe Karla -- in a book that is, I believe, the single finest piece of spy fiction ever written.

You're probably starting to realize how much I enjoy history. I read, at least partially, for a sense of escape. I want to get away from my corporate day job where people feel the need to invent replacements for perfectly good words (e.g. saying "we'll go ahead of the ask succeeds and we get funding" rather than the perfectly good and well seasoned word request). But I digress. No world is more bizarre and alien than the 14th century. And given that I just pushed through a few science fiction novels, that is saying something!

You're probably starting to realize how much I enjoy history. I read, at least partially, for a sense of escape. I want to get away from my corporate day job where people feel the need to invent replacements for perfectly good words (e.g. saying "we'll go ahead of the ask succeeds and we get funding" rather than the perfectly good and well seasoned word request). But I digress. No world is more bizarre and alien than the 14th century. And given that I just pushed through a few science fiction novels, that is saying something! One day, before I die, I would like to understand everything in this book. I suspect that, when that happens, I will quietly dissolve into a vaporous cloud of disassociating particles. Fortunately, it will take quite a long time for that to occur.

One day, before I die, I would like to understand everything in this book. I suspect that, when that happens, I will quietly dissolve into a vaporous cloud of disassociating particles. Fortunately, it will take quite a long time for that to occur. What could be better than a book that is simultaneously about science and cooking? Very few things, I tell you that, when the book has the lucid explanations, beautiful production, and sweeping scope of On Food and Cooking. As an aside, you many have noticed just how often the word sweeping shows up as a word of praise in this entry (at least I think it does!). I tend to like my non-fiction that way: broad, epic, profound. I'm a generalist, I suspect, and like situations that let me see as broad a scope as possible. I also relish the moment of connection when seemingly disparate threads merge into a single coherent story.

What could be better than a book that is simultaneously about science and cooking? Very few things, I tell you that, when the book has the lucid explanations, beautiful production, and sweeping scope of On Food and Cooking. As an aside, you many have noticed just how often the word sweeping shows up as a word of praise in this entry (at least I think it does!). I tend to like my non-fiction that way: broad, epic, profound. I'm a generalist, I suspect, and like situations that let me see as broad a scope as possible. I also relish the moment of connection when seemingly disparate threads merge into a single coherent story.

It was stickered as coming from the Stanford Alumni association and turned out to contain an interesting object called a "Reunion Book." I'd never heard of one of these before, so I assume that some of you are as ignorant as I was. It is a sort of reverse-yearbook, a "where are we now" of all the people you entered college with. Or graduated with. Or should have graduated with. I haven't really explored the details.

It was stickered as coming from the Stanford Alumni association and turned out to contain an interesting object called a "Reunion Book." I'd never heard of one of these before, so I assume that some of you are as ignorant as I was. It is a sort of reverse-yearbook, a "where are we now" of all the people you entered college with. Or graduated with. Or should have graduated with. I haven't really explored the details.  Direct 2.0 is an interesting plan to take the same basic ground rules that the Constellation office bungled into the Orion capsule and the Aries booster family: re-use hardware, be fast, be cheap, be safe, be political. For some reason, they appear to make work what ATK and the guys at JSC have turned into one of the most profound cases of "throwing good money after bad" that I've seen since Pets.com collapsed. Now granted, when it first showed up on ATK's website, the Aries idea, the stick and the...well...whatever the other thing is called...seemed like potentially elegant approaches to getting people into space. And since the my, oh my, what a pattern of unrelenting growth and going-to-hell-ness. For the big boy, four engines...then five...now six...and ever more segments into the solid rocket motors. For the stick first rampant weight growth, then the oddly Mercury/Redstone like non-sustainable orbit that requires a service module boost almost immediately after separation, and now the crisis of ensuring that the astronauts are not jiggled into jelly by some sort of multi-million dollar paintshaker. Solve by...what...putting the parachutes on springs so they damp out the oscillations? OK, I'm perfectly comfortable with the theory and accept that the paradamper is a better idea that the absurd notion of the highly scarfed OMS engines firing in time to damp the oscillations, but this sort of solution is what I'm using to prevent my washing machine from shaking the house when it hits a spin cycle.

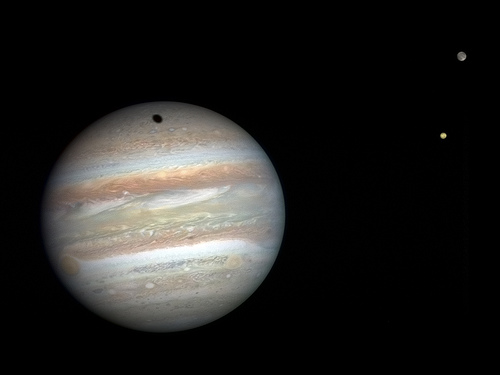

Direct 2.0 is an interesting plan to take the same basic ground rules that the Constellation office bungled into the Orion capsule and the Aries booster family: re-use hardware, be fast, be cheap, be safe, be political. For some reason, they appear to make work what ATK and the guys at JSC have turned into one of the most profound cases of "throwing good money after bad" that I've seen since Pets.com collapsed. Now granted, when it first showed up on ATK's website, the Aries idea, the stick and the...well...whatever the other thing is called...seemed like potentially elegant approaches to getting people into space. And since the my, oh my, what a pattern of unrelenting growth and going-to-hell-ness. For the big boy, four engines...then five...now six...and ever more segments into the solid rocket motors. For the stick first rampant weight growth, then the oddly Mercury/Redstone like non-sustainable orbit that requires a service module boost almost immediately after separation, and now the crisis of ensuring that the astronauts are not jiggled into jelly by some sort of multi-million dollar paintshaker. Solve by...what...putting the parachutes on springs so they damp out the oscillations? OK, I'm perfectly comfortable with the theory and accept that the paradamper is a better idea that the absurd notion of the highly scarfed OMS engines firing in time to damp the oscillations, but this sort of solution is what I'm using to prevent my washing machine from shaking the house when it hits a spin cycle. But above the practical NASA-like issues here, there is a phenomenal message that an official endorsement of Direct 2.0 would send. It would signify, perhaps more than anything, the Coming Of The Internet. The flattening of the world that has been written about so often would splash down in the waters of the American space program. Already us out there on the Internet have helped out those who will listen, starting with the incomparable Alan Stern and his New Horizons team who gratefully accepted the suggestions of several fans as to how to construct the Kodak Moment shots as their little probe sped through the Jovian system.

But above the practical NASA-like issues here, there is a phenomenal message that an official endorsement of Direct 2.0 would send. It would signify, perhaps more than anything, the Coming Of The Internet. The flattening of the world that has been written about so often would splash down in the waters of the American space program. Already us out there on the Internet have helped out those who will listen, starting with the incomparable Alan Stern and his New Horizons team who gratefully accepted the suggestions of several fans as to how to construct the Kodak Moment shots as their little probe sped through the Jovian system.  The science team was understandable busy focusing on the real scientific observations. Knowing this, they listened when folks at home punched the probe's trajectory data into computer simulators and came up with the times and pointing angles necessary to get the spectacular shots of Jupiter and its moons that made the front pages. The tools are no longer beyond the reach of the ordinary, interested, outsider. The interest has always been there. If you will let us in, you'll find that we are not just a nuisance but a powerful, useful force. Welcome us.

The science team was understandable busy focusing on the real scientific observations. Knowing this, they listened when folks at home punched the probe's trajectory data into computer simulators and came up with the times and pointing angles necessary to get the spectacular shots of Jupiter and its moons that made the front pages. The tools are no longer beyond the reach of the ordinary, interested, outsider. The interest has always been there. If you will let us in, you'll find that we are not just a nuisance but a powerful, useful force. Welcome us. This is all about rockets. Exploding rockets, to be precise. Rockets that collide with themselves and then proceed to fall apart, to be progressively more precise. Rockets that do so because of design errors that people on Internet chat sites are able to spot before the engineers who designed the rocket are. Granted, these are chat sites populated by rocket engineering professionals, but still!

This is all about rockets. Exploding rockets, to be precise. Rockets that collide with themselves and then proceed to fall apart, to be progressively more precise. Rockets that do so because of design errors that people on Internet chat sites are able to spot before the engineers who designed the rocket are. Granted, these are chat sites populated by rocket engineering professionals, but still! You can't upload software to a rocket in flight and correct the mixture ratio of your main engine. Not in the 2:55 long first stage burn. You have to get it right, straight away. But the software mindset knows that you can debug. You have to debug. You code and test and code and test and launch and code and test and code and relaunch. The rocket mindset codes and tests and codes and tests and codes and tests...again and again and again and again. True mission critical software design involves parallel development teams (working in isolation to prevent communication and the formation of similar assumptions). True mission critical design involves multiple layers of check and recheck. Recheck checkers check the recheckers.

You can't upload software to a rocket in flight and correct the mixture ratio of your main engine. Not in the 2:55 long first stage burn. You have to get it right, straight away. But the software mindset knows that you can debug. You have to debug. You code and test and code and test and launch and code and test and code and relaunch. The rocket mindset codes and tests and codes and tests and codes and tests...again and again and again and again. True mission critical software design involves parallel development teams (working in isolation to prevent communication and the formation of similar assumptions). True mission critical design involves multiple layers of check and recheck. Recheck checkers check the recheckers. A very telling moment that I know well is the pre-launch instructions that show up just before the release from final hold at, I believe, T-6:00 during an Atlas V countdown. The Atlas V is one of the most well engineered and well processed of "old school" boosters. Their countdowns are always flawless and their nearly always so (they had a one-time hiccup with a bad valve in an engine that resulted in off-nominal orbit injection). Even though everyone has done it probably a hundred times in rehearsal, the launch director runs through a litany of instructions, drills to cover launch, abort, recycle, and communications during the final seconds. They know it but it is repeated to remind and to ritualize.

A very telling moment that I know well is the pre-launch instructions that show up just before the release from final hold at, I believe, T-6:00 during an Atlas V countdown. The Atlas V is one of the most well engineered and well processed of "old school" boosters. Their countdowns are always flawless and their nearly always so (they had a one-time hiccup with a bad valve in an engine that resulted in off-nominal orbit injection). Even though everyone has done it probably a hundred times in rehearsal, the launch director runs through a litany of instructions, drills to cover launch, abort, recycle, and communications during the final seconds. They know it but it is repeated to remind and to ritualize. And, right as you'd expect, just as dinner was served, they hit the classic T-minus-ten point over in Kwajelan. So I wandered outside with the MacBook and reported on the update -- that the thing had shut itself down on the pad. C & J were happy to let me fill them in on they brief history of SpaceX and why this was sort of a big deal -- why I felt that if any of the alt.space crew was going to do it, it was Elon. A little blend of damn-the-torpedos, a little bit of willingness to take it on the chin and admit the hubris of their first vision.

And, right as you'd expect, just as dinner was served, they hit the classic T-minus-ten point over in Kwajelan. So I wandered outside with the MacBook and reported on the update -- that the thing had shut itself down on the pad. C & J were happy to let me fill them in on they brief history of SpaceX and why this was sort of a big deal -- why I felt that if any of the alt.space crew was going to do it, it was Elon. A little blend of damn-the-torpedos, a little bit of willingness to take it on the chin and admit the hubris of their first vision. We settled in to play the very fun German style game "Settlers of Catan" that we had recently purchased. Erica went on to win both rounds -- though Colin gave her a good run for her money on the first one and I did a passable job of chasing on the second and might have come closer if Colin hadn't made a trade with Erica that basically gave her the game. But it was 1:20 and we were all tired. What was great was hanging out until that late with my favorite people playing a great game and having a lot of really good laughs.

We settled in to play the very fun German style game "Settlers of Catan" that we had recently purchased. Erica went on to win both rounds -- though Colin gave her a good run for her money on the first one and I did a passable job of chasing on the second and might have come closer if Colin hadn't made a trade with Erica that basically gave her the game. But it was 1:20 and we were all tired. What was great was hanging out until that late with my favorite people playing a great game and having a lot of really good laughs. called

called