But I digress from a point I have not yet started to make.

Conceptually, the LCS is clever. It is designed to offer a game changing degree of modularity, and this modularity allows for a striking range of capabilities to fit in a single hull -- without that hull getting so large that it grows unwieldy and incapable of the in-shore mission. And (perhaps more importantly these days) without having to buy enough gear to equip every hull equally. The math, at this point, seems entirely sound -- the chances of needing to simultaneously land a SEAL team, sweep for mines, and hunt submarines are pretty slim. So build a bunch of ships that can't do all of these things at once and just enough gear to go around, one kit per vessel. You cross-deck the sonar arrays depending on which ship is tasked with sub hunting. Cross-deck the minehunting robots to the needed ships, the special ops kit, etc. all as needed.

The modularity carries with it a drawback -- the fact that these modules need to be changed. I mean, what if you do suddenly need to hunt submarines? Fine, go in to port, swap out the launching ramp and the rubber boats, and the gym and barracks for the SEALS. Load aboard the towed array sonar kit. Fly off the MH-60's that were doing the special ops work and land a couple of SH-60's to drop torpedos and do sonar dips. Let the SEALS go drink some beer and bring on board some mine warfare experts. Lather, rinse, and repeat of the mission changes again.

Great plan, provided you have a friendly port nearby. And, with a bit of a flourish, the drawback to the whole LCS falls in to place. It truly is designed for the current war. By which I mean the Persian Gulf -- a place where it is never too far from a friendly port where it can meet up with a tender for supply and conversion between roles. Which also means, of course, that though capable on paper of some fantastic speeds, the LCS' true speed of deployment is limited by the rate at which logistic support can be brought over to resupply and re-role the vessel when needed.

Now modern navy's have always depended on supply lines -- and since the US Navy perfected underway replenishment during and after World War Two, the need for friendly foreign bases has been much reduced. I fear that the LCS will only take us back a stage, back to the era of the coal fired navy when allied ports were needed every few thousand miles, ready to refill the hungry bunkers of those early, inefficient vessels. Commodore Perry, anyone?

I am as optimistic as the next person that the Obama administration's policies will see a return towards the coalition building that dominated the war fighting of the past few decades -- when the US was working as a member (all be it a dominant one) of a team and could, therefore, pretty reliably count on friendly ports for its efforts. But even so, this reliance has its costs and risks. Does the USS Cole bring back any memories?

Or, to bring up a more timely situation, what about Somalia and the shindiggery going on in the waters of East Africa? More on that later.

Much of naval warfare is about maintaining presence. That is the thing, in this globalized world, that navies can do better than any other branch of the services. A ship can, in a way that no other weapon system can, simply be. It can hang out, outside the twelve mile limit and in international waters, just saying a friendly "hi." The sort of "hi" that can carry Tomahawk missiles (and therefore reach just shy of 1,000 nautical miles inland in the latest version), soak up radio and radar signals and send them back home to the NSA boffins, keep track of hostile or suspect shipping. It is the very epitome of "speak softly and carry a big stick," it is the reason the phrase "gunboat diplomacy" has not been replaced with the phrase "uncrewed air vehicle diplomacy." A warship, or a collection of them, can maintain free passage of the sea lanes that carry the overwhelming majority of the world's commerce...or close them off when blockade and embargo is the order of the day.

The United States Navy currently possess the most capable and versatile floating big sticks in the military world -- the largest fleet of (and the largest) air craft carriers in the world. There are also dozens of CG-47 and DDG-51 class cruisers and destroyers, all with exactly the sort of staying power and strike capability that I'm talking about. Boo-ya. Fly Navy.

But these are big assets -- and many are tied up in the odd sort of self-escorting that is the devil of all deployed military operations. The cruisers are busy escorting the carriers, protecting them, tending to them. All of these vessels are also forward deployed, with their unique and amazing capabilities, around countries like North Korea that have a disturbing to just go ballistic one day (pardon the pun) or fighting the couple of active wars in which we are currently embroiled. Not a lot of these high-ticket ships are left to fill in the little cracks in US foreign policy.

Like Somalia.

There was once a great and noble fleet of Perry class frigates (a different Perry, not the Commodore who opened up Japan), but these little and versatile ships are rapidly disappearing and now less than half of those built remain in US Navy service. Just to give you an idea of the sort of missions that these ships are tasked with, let me relate the history of one particular Perry class frigate, the USS Nicholas, during Gulf War Senior. Now I don't want you to think that I'm disrespecting the contributions of the decks launching strike missions or the cruisers launching Tomahawks. But while these "big guns" stood back and did their deeds from a distance, the Nicholas found herself:

There was once a great and noble fleet of Perry class frigates (a different Perry, not the Commodore who opened up Japan), but these little and versatile ships are rapidly disappearing and now less than half of those built remain in US Navy service. Just to give you an idea of the sort of missions that these ships are tasked with, let me relate the history of one particular Perry class frigate, the USS Nicholas, during Gulf War Senior. Now I don't want you to think that I'm disrespecting the contributions of the decks launching strike missions or the cruisers launching Tomahawks. But while these "big guns" stood back and did their deeds from a distance, the Nicholas found herself:1) recapturing the first piece of Kuwait, an oil platform, and in the process capturing the first Iraqi prisoners of the war.

2) detecting and (in cooperation with a Royal Navy frigate of similar size and their embarked helicopters) sinking about a dozen Iraqi patrol boats.

3) rescuing a downed USAF pilot

4) accidentally being shot at by another USAF pilot (no harm done)

5) destroying several Iraqi laid mines

6) escorting the battleships Missouri and Wisconsin on gunfire missions.

During much of this conflict she was operating 70 miles closer to enemy shores than any other "regular" US Navy vessel. Since then she's kept on with the busy agenda. Read the Wiki page. Oh, and just to brag, ships that share my name have a bit of a history. If you really want a busy naval career, look at the 2nd USS Nicholas (the one I was just writing about was the third).

Now here's where I get to my point -- that list of accomplishments, from Iraq to Bosnia, is a litany you will find on few vessels twice her size. It is an irony of naval history that very often the big ships do not get the big missions.

As the Perrys fade away, proving too expensive to update and too expensive to crew, the LCS' are supposed to be coming online to fill the gap. Well, the Zumwalt is supposed to be as well -- but did anyone catch the price tag there? $3.3 billion. Yes, and perhaps more. That's the reason the big ships don't do exciting things. They cost too much. The Zumwalt is also easily the ugliest warship that anyone has ever contemplated building. Just say "no" to tumblehome, people.

As the Perrys fade away, proving too expensive to update and too expensive to crew, the LCS' are supposed to be coming online to fill the gap. Well, the Zumwalt is supposed to be as well -- but did anyone catch the price tag there? $3.3 billion. Yes, and perhaps more. That's the reason the big ships don't do exciting things. They cost too much. The Zumwalt is also easily the ugliest warship that anyone has ever contemplated building. Just say "no" to tumblehome, people.But the little ships -- the new ones, the LCS -- run the risk of simply creating more trouble by requiring more basing, more supply lines, and more reasons to maintain a presence in the first place. It is just a return to the problem of spending so many of your resources protecting and supporting your resources that we you have no resources left to actually do anything.

Do I have a solution, or am I just a crank?

Actually, I have a solution. At one level, this solution is simply "more Perrys." More medium sized vessels, handy enough to operate in the littorals, large enough to play a role in a deep ocean fight and to help with the escort needs of the 1st class navy (carriers, cruisers, amphibious vessels), affordable enough to be built in quantities sufficient to send them where needed, large enough to be self supporting for a reasonable length of mission. Part of what made the Perrys such versatile vessels was that they were just big enough to take on all sorts of odd adjuncts for their interesting missions. During her Gulf War stint, the Nicholas was carrying a Navy SH-60B helicopter, two Army OH-58D helicopters, an add-on infrared sight system (such things are now common), a kluged together minehunting sonar, and a handful of Navy SEALs to do the dirty work that occasionally came along. It had to have been a crowded ship...but it held up.

Currently US shipbuilding is leaving this size range empty. The overly-small LCS hulls are being built, production slowly ramping up to speed. And the fugly Zumwalts are out there, somewhere, presumably striking fear and nightmares into shipyard workers forced to build them.

So for my solution I am going to turn to the French. Yes, the French. Mocked in American military circles for so many reasons (many of which are undeserved, or at least more reasonable when explored in some depth...e.g. why did the French accumulate such a reputation for capitulation and inaction...it might have something to do with a reaction to loosing 1.4 million dead and 4.3 million wounded in World War One while pursuing a strategy of "offensive above all else"...but that is a topic for another blog). But they are a nation of increasingly competent engineering -- even if it is occasionally different in art and concept than that produced by this nation.

The French are facing a similar problem, actually, their own need to maintain a sustained global presence. Ever since the days of de Gaulle, France has styled herself as a "mini superpower," wanting all of the trappings and abilities of the United States and the Soviet Union, all be it in miniature. And so France is one of the few countries of Europe that has always sought to maintain a global capability of power projection. This goal has not always been successful and many struggling deployments exposed weaknesses (much as the Falklands campaign exposed in the English).

As touches mid-size naval combatants (which is the point of this now much diverted blog), France had some interesting and moderately successful experiments with not-quite-warships in the form of the Floreal class, an odd sort of mini-frigate with a disproportionally large helicopter hangar (actually a normal size helicopter hangar on a ship that was by conventional measure "too small" to support it). The resulting package was perfect for low-level flag showing, cooperative work, blockading, etc. But it didn't quite have the chutzpa do really rumble with the real warships and only six were built. The Floreal was half of what I'm looking for -- sustained presence and enforcement, but not enough warfighting.

But facing the obsolescence of several other frigate-sized vessels, and an almost dramatically unsuccessful Franco-Enlish alliance to build an anti-aircraft destroyer, the French got together with the Italians (similar needs, if not quite of the same scale) and produced the FREMM. That stands for something, FREMM, presumably in French but possibly in Italian, that roughly means "European Multi-Mission Frigate." I have found, by the way, that French acronyms are often very nearly (and occasionally exactly) opposite the same acronym in English. So perhaps it is actually "Multi Mission European Frigate" and they kept the R from FRigate in there so it wouldn't be named "femm" which would be too close to "femme" for everyone's comfort. I'm not sure.

The first hull of these new ships to be built for the French is to be the Aquitaine which is a truly beautiful word and much easier to say that "FREMM" and so, even if it is harder to type, I will hereafter call these ships the Aquitaine class.

Now for starters, the Aquitaine is beautiful in a way that very few modern warships are. Boxy, yes, but somewhat less so than many of her peers. The long low foredeck gives a nice pointy look, not quite as Cigarette Boat as the LCS, but perhaps more evocative of the WWII era battleships and cruisers with their long gun covered bows. In a Walter Mitty sort of way, I can picture North (or South) Atlantic (or Pacific) seas dashing back as the bow buries itself in a wave, spray flying aft against the pilothouse windows (and of course, there is Commander Nick, cup of coffee in hand, standing on the heaving deck, scanning the horizon...).

Now for starters, the Aquitaine is beautiful in a way that very few modern warships are. Boxy, yes, but somewhat less so than many of her peers. The long low foredeck gives a nice pointy look, not quite as Cigarette Boat as the LCS, but perhaps more evocative of the WWII era battleships and cruisers with their long gun covered bows. In a Walter Mitty sort of way, I can picture North (or South) Atlantic (or Pacific) seas dashing back as the bow buries itself in a wave, spray flying aft against the pilothouse windows (and of course, there is Commander Nick, cup of coffee in hand, standing on the heaving deck, scanning the horizon...).Ahem, back to my morning train ride.

And besides, this is about naval strategy and procurement and not about romanticized places-I'd-rather-be...

At this point I am going to consciously avoid the trap of rattling off a catalog of meaningless statistics about what sorts of missiles are tucked where and how many shells the gun can fire in a minute's time. Generally, these are academic details. In nutshell-land, it would break down like this, going from fore to aft:

Gun for protection against aircraft or, even more critically, small/medium sized boats as are so often used by developing nations and terrorists.

Bank of missiles, some anti-aircraft for self protection and some strike for targeting deep inland.

Bundle of anti ship missiles.

A few odd smaller guns for defense against more of the small-random-boat sort of threat.

LOTS of decoys against missiles, torpedos, etc.

A couple of torpedos to deal with sneaky submarines.

A big hanger and helicopter pad for all the wonderful versatility that helicopters bring to medium-sized warships.

Tucked away is a surprisingly competent sonar system, on par with the best in the world. I say "surprising" because anti-submarine warfare is generally out of fashion among the navies of the West -- and has been so ever since the evaporation of the Soviet threat. That sonar is an important part of why I so like the Aquitaine -- a respectful inclusion of anti-submarine capability. Right now, the US Navy is letting much of its ASW capability go. Granted, the big-bad Soviet submarine force is in decay (with a tendency to catch fire, sink, or sit on the stocks for a decade or two half completed) and their new-building programs have tended to produce more ominous news reports than completed submarines.

But there are other threats out there, and in coastal waters a small submarine, such as those that are proliferating in the developing world, can be a potent force of ambush if well handled. And the proliferation of AIP's means that the sustained submerged endurance that was long the sole province of the nuclear navies (US, UK, France, China, Russia, and occasionally India) has spread. So another highly capable ASW hull is a (sorry Martha) Good Thing.

There is the usual complement of radars and a very capable electronic warfare suite (that IS a lot of antennas you see). I'm not barreling into details because the exact make and model of each piece of hardware is frankly boring. The overall picture, the synergy, is what counts. And here is what that synergy is:

A medium sized, versatile warship. One capable of providing world-class anti-sumbarine efforts from deep ocean escort to hunting diesel boats in the shallows. One capable of protecting itself from air threats and of minimally extending that protection to other vessels. One capable of projecting its sphere of influence and observation beyond the horizon (fancy way of saying "carrying a helicopter"). And, uniquely for its size, one capable of projecting the big-stick-factor several hundred miles inland, for the Scalp Naval will have capabilities not too far removed from the well known Tomahawk cruise missile. So take that persistence I've talked about and notch it up one.

An Americanized Aquitaine would obviously show changes. Swap missiles around (out go ASTERS and Scalp Naval, in go ESSMS and TacTom). Fiddle the radars so you have guidance for the ESSMS'. Whatever. Gain a bit here, loose a bit there. I'm not even going to get involved in the holy war that is medium calibre gun selection. Pick your favorite. The US is gravitating towards Swedish 57mm's, the Aquitaine has an Italian 76mm. Personally, there ain't no replacement for displacement (which is NASCAR for "bigger guns are better").

I'd (and this is a controversial one) actually not replacing the Exocet anti ship missiles with their American counterparts (a weapon called Harpoon). I'm actually only aware of a Harpoon being fired in anger twice, once in the 1980's and once in 1991's original Gulf War. Tac-Tom has a nominal moving target capability and I'd rely on that, saving a few bucks of purchase cost, hours of maintenance, and tons of displacement.

The big helicopter deck is a crucial asset -- the no-hanger DDG-51's taught the US Navy to never again build a large combatant without helicopter capabilities. Particularly in today's small-to-medium size wars, the ability to extend the ship's horizon by anything from a few dozen to a hundred miles provides much of the reach necessary for patrolling and enforcement.

This is, in a very real sense, a return to the role of the Frigate as it was two hundred years ago. A ship capable of holding its own in battle, of fighting amongst and supporting the larger vessels when the conflict reaches "large" size. But a ship optimized for cruising, for endurance at sea and for flexibility in employment. A ship that could support a low level conflict off the coast of a nascent African nation (my Somalia riff again) or anywhere else without requiring controversial or vulnerable ports. A ship capable of maintaining a presence, for purposes of force or policy, of acting when necessary in offense or defense, of protecting interests at sea or on land.

Now I'm not insisting that, right now, the DoD slap down 500-600 million US$ for each of thirty or forty of these ships. I'm a blogger, and therefore have little power to actually insist anything. But here's how things stand -- the LCS was supposed to run about $240 million each and is currently about 100% over budget (and swelling). The Aquitaines are supposed to cost $510 million each. Given the lower technical risk of the less "game changing" design, I'd estimate the chances of cost growth on the FREMM project to be a lot less, say 20%. And the LCS bugs will get ironed out until they cost, say, $350 million each. That would allow for building roughly 32 Aquitaine class vessels for the cost of the planned 55 LCS vessels. 32 vessels with much greater staying power, versatility, adaptability, and utility. And 32 vessels that will not hamstring the navy with increased basing requirements, shorter endurances, and yet more vulnerable and expensive supply lines. Furthermore, with sufficient size, crew, endurance, and capability, the Aquitaine would free up some big DDG-51 and CG-47 vessels, allowing them to operate at somewhat reduced tempos or to focus on global crisis states such as North Korea and its nascent ballistic missile capability.

I don't care how this is implemented. The Aquitaine is pretty and presents exactly the sort of blend that I think a vessel of this class needs (the strategic strike role is genius). But I do know what one of the major hurdles will be -- the submarine force. Facing the same threat of "why do we have them" as other cold war naval assets (reference above on decline of Big Red's submarine forces), the sub guys have pointed out three roles for which they are excellently suited: anti-submarine warfare, strategic strike, and special operations. These are all true -- these are excellent roles for a submarine. But the wonderful nuke boats are expensive to operate, a limited asset numerically, but worst of all their ace card, their stealth, denies them the ability to provide presence. But an Americanized Aquitaine would threaten two (actually all three) of these roles and therefore face opposition from the silent service. Well, no good idea ever went unopposed, and if Gates is willing to face down The Admirals and The Generals over some of the other elements of his agenda, perhaps he can fight this one for me. Besides, there are a lot more naval officers who are going to see surface commands (and therefore have a vested interest in a surface navy) than will ever see an undersea command.

The result of all of this?

Not, perhaps a potential game changer, but a solid and adaptable performer. Something perfectly suited to the crucial need for naval presence in times and places of peace, crisis, and war.

A ship that would enable more projection, and less dependance.

A classic frigate for the 21st century.

The first thing that got these musings started was an article in Aviation Week that a

The first thing that got these musings started was an article in Aviation Week that a  Never the less, this illustrates one of the projected directions of modern air war. Un-crewed (we don't say "unmanned" any more) air vehicles have the wonderful ability to stay on scene for hours and hours and hours -- days even. A Reaper can loiter for NN hours, a Global Hawk for 40 to 48, and that latter figure after flying a 3,000nm round trip from home field to target area. This kind of sustained presence is invaluable in brining the areal perspective to the kind of fight going on in Iraq and Afghanistan. The traditional fast mover can offer little but responsive firepower -- heading in from a loitering point when called for by guys on the ground and depending on them for direction and guidance. Even maintaining that kind of ability -- a "cab rank" of close air support -- requires a couple of dozen aircraft in the field, tankers, and a rotating (and expensive) presence.

Never the less, this illustrates one of the projected directions of modern air war. Un-crewed (we don't say "unmanned" any more) air vehicles have the wonderful ability to stay on scene for hours and hours and hours -- days even. A Reaper can loiter for NN hours, a Global Hawk for 40 to 48, and that latter figure after flying a 3,000nm round trip from home field to target area. This kind of sustained presence is invaluable in brining the areal perspective to the kind of fight going on in Iraq and Afghanistan. The traditional fast mover can offer little but responsive firepower -- heading in from a loitering point when called for by guys on the ground and depending on them for direction and guidance. Even maintaining that kind of ability -- a "cab rank" of close air support -- requires a couple of dozen aircraft in the field, tankers, and a rotating (and expensive) presence. Only the guy-with-rifle can clear a stairwell without blowing up the building. Only the guy-with-rifle can rifle through the papers in a bomb-maker's hide looking for contacts. Only the guy-with-rifle can snap interconnected zip-ties across someone's wrists and send him back across the lines. Only the guy-with-rifle can man a roadblock or walk the streets on a dismounted patrol. Only the guy-with-rifle can use his wits and his skill in their purest form to go, see, and report with an intimacy with which no sensor package can compete. And, in the nicer side of the military, only the man-with-rifle can put down that gun and unload supplies or build schools or clear rubble or help the wounded or any of those humanitarian moments.

Only the guy-with-rifle can clear a stairwell without blowing up the building. Only the guy-with-rifle can rifle through the papers in a bomb-maker's hide looking for contacts. Only the guy-with-rifle can snap interconnected zip-ties across someone's wrists and send him back across the lines. Only the guy-with-rifle can man a roadblock or walk the streets on a dismounted patrol. Only the guy-with-rifle can use his wits and his skill in their purest form to go, see, and report with an intimacy with which no sensor package can compete. And, in the nicer side of the military, only the man-with-rifle can put down that gun and unload supplies or build schools or clear rubble or help the wounded or any of those humanitarian moments. Any given guy-with-rifle might now carry a personal radio and GPS receiver, a laser rangefinder, night vision gear, and a short range guided missile -- all gear inconceivable as personal equipment even twenty years ago. His rifle might have a laser spot projector for nighttime target marking, a flashlight, a grenade launcher, and a 4-power scope clamped and strapped to it. He may wear protective gear offering protection unheard of to previous generations of soldiers. But all of this goes to underscore not his budding obsolescence at the hands of impending robotic marvels but rather continued -- or even increased -- importance.

Any given guy-with-rifle might now carry a personal radio and GPS receiver, a laser rangefinder, night vision gear, and a short range guided missile -- all gear inconceivable as personal equipment even twenty years ago. His rifle might have a laser spot projector for nighttime target marking, a flashlight, a grenade launcher, and a 4-power scope clamped and strapped to it. He may wear protective gear offering protection unheard of to previous generations of soldiers. But all of this goes to underscore not his budding obsolescence at the hands of impending robotic marvels but rather continued -- or even increased -- importance. All of this makes one thing clear -- the rifleman is here to stay. The reasons for this emphasis shift are obvious -- increasing expectation of urban fighting, prevalance of counter-insurgency fighting, peacekeeping operations where forces work close to the civilian populations rather than in an open field battle -- are obvious and clear to anyone who watches the news. Tanks are retreating from their role as the unstoppable bohemouth's of the battlefield back to the role of supplying escort, protection, and covering fire for the infantry for which they were originally concieved. Air power is threatening to obsolete itself, metamorphosing (at least partially) from resplendant knights of the air into remote control spotters sitting in air-conditioned control vans thousands of miles from conflict.

All of this makes one thing clear -- the rifleman is here to stay. The reasons for this emphasis shift are obvious -- increasing expectation of urban fighting, prevalance of counter-insurgency fighting, peacekeeping operations where forces work close to the civilian populations rather than in an open field battle -- are obvious and clear to anyone who watches the news. Tanks are retreating from their role as the unstoppable bohemouth's of the battlefield back to the role of supplying escort, protection, and covering fire for the infantry for which they were originally concieved. Air power is threatening to obsolete itself, metamorphosing (at least partially) from resplendant knights of the air into remote control spotters sitting in air-conditioned control vans thousands of miles from conflict. 2008's been a bad year for the Air Force. We lost a B-52 and her crew today -- an airplane that was flying for probably 45 years, flew during (though not necessarily in) five or so wars, and had probably outlasted the first men to sit in her cockpit. Now granted, military flying is always dangerous and 45 year old airplanes carry their own dangers. But we are talking about a type with one of the best records in the Air Force -- probably not least because all the bugs had been worked out by now!

2008's been a bad year for the Air Force. We lost a B-52 and her crew today -- an airplane that was flying for probably 45 years, flew during (though not necessarily in) five or so wars, and had probably outlasted the first men to sit in her cockpit. Now granted, military flying is always dangerous and 45 year old airplanes carry their own dangers. But we are talking about a type with one of the best records in the Air Force -- probably not least because all the bugs had been worked out by now! So that's my question -- who is minding the store over there? Whoever you are, let me tell you that General Le May wouldn NOT be proud. You'd all have found yourself off flight duty and given a dressing down that even Admiral Rickover would have admired. I know I'm jumping to conclusions, but this isn't about a single crash -- its about something that seems too significantly clustered to be mere coincidence. And non-coincidences demand a search for universal causes.

So that's my question -- who is minding the store over there? Whoever you are, let me tell you that General Le May wouldn NOT be proud. You'd all have found yourself off flight duty and given a dressing down that even Admiral Rickover would have admired. I know I'm jumping to conclusions, but this isn't about a single crash -- its about something that seems too significantly clustered to be mere coincidence. And non-coincidences demand a search for universal causes. It is now time for the second and third of my promised favorite ciphers. And, just to let you know, I am now planning on creating an entry for Vic cipher and some of the other very elaborate spy ciphers of the cold war. Operationally Vic and its cousins were not effective for the field -- requiring too much precision, time, and care and training for a field radio operator or cipher clerk who may well be working under fire. The importance of ensuring that ciphers can realistically be used in field conditions sometimes escapes the notice of the experts charged with developing cipher systems. As we will see, this weakness played an important role in undermining one of the ciphers planned for study today. ADFGVX, on the other hand, certainly can be implemented under field conditions.

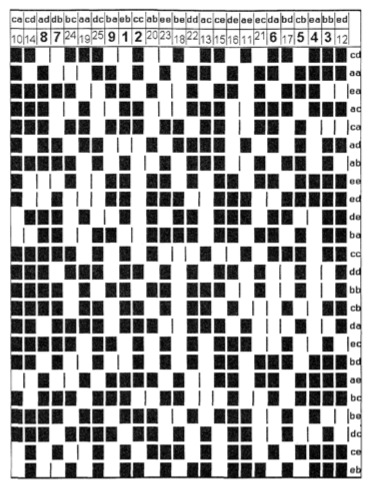

It is now time for the second and third of my promised favorite ciphers. And, just to let you know, I am now planning on creating an entry for Vic cipher and some of the other very elaborate spy ciphers of the cold war. Operationally Vic and its cousins were not effective for the field -- requiring too much precision, time, and care and training for a field radio operator or cipher clerk who may well be working under fire. The importance of ensuring that ciphers can realistically be used in field conditions sometimes escapes the notice of the experts charged with developing cipher systems. As we will see, this weakness played an important role in undermining one of the ciphers planned for study today. ADFGVX, on the other hand, certainly can be implemented under field conditions. Though I titled this thread of blogging "My Favorite Cipher," and I am a big fan of ADFGVX and find something nifty about the simple tables of Dockyard, I don't particularly like the Rasterschlüssel. It is a transposition cipher alone -- something which a certain truthiest superstition tells me can't possibly be as secure as a mix of transposition and substitution (remember -- diffusion and confusion) as used by ADFGVX. How can it be, I just feel, that a cipher that preserves all the right letters can have the security of one that changes them? Just move then around -- like a big word scramble!

Though I titled this thread of blogging "My Favorite Cipher," and I am a big fan of ADFGVX and find something nifty about the simple tables of Dockyard, I don't particularly like the Rasterschlüssel. It is a transposition cipher alone -- something which a certain truthiest superstition tells me can't possibly be as secure as a mix of transposition and substitution (remember -- diffusion and confusion) as used by ADFGVX. How can it be, I just feel, that a cipher that preserves all the right letters can have the security of one that changes them? Just move then around -- like a big word scramble!

en pilots were real pilots, engineers were real engineers (and let's not forget the small furry creatures from Alpha Centuri -- they were real too!).

en pilots were real pilots, engineers were real engineers (and let's not forget the small furry creatures from Alpha Centuri -- they were real too!).

Eventually things get less interesting. The Navy, in particular, starts to carve the information up into classified and non-classified sections. The aircraft, military and commercial, get sufficiently complex that the reading gets denser and denser. Still fascinating, from the airplane lover standpoint, but no longer the full retro experience on top. Thing hit their nadir, probably, in the Navy's current manual for the F/A-18, a volume so dryly procedural and simultaneously obtuse and neurotically obsessed with minutiae as to read like Tolkien's Silmarillion, only without the elves. Boeing's current commercial offerings are no better -- the 767's and 777's reading more like giant VCR manuals than the sort of in-depth technical examination that I enjoy -- and I tend to believe a qualified pilot needs. It is as if the F/A-18 manual substitutes prepared drills for every contingency for actual understanding and the 767 and 777 manuals are afraid of spilling any corporate secrets.

Eventually things get less interesting. The Navy, in particular, starts to carve the information up into classified and non-classified sections. The aircraft, military and commercial, get sufficiently complex that the reading gets denser and denser. Still fascinating, from the airplane lover standpoint, but no longer the full retro experience on top. Thing hit their nadir, probably, in the Navy's current manual for the F/A-18, a volume so dryly procedural and simultaneously obtuse and neurotically obsessed with minutiae as to read like Tolkien's Silmarillion, only without the elves. Boeing's current commercial offerings are no better -- the 767's and 777's reading more like giant VCR manuals than the sort of in-depth technical examination that I enjoy -- and I tend to believe a qualified pilot needs. It is as if the F/A-18 manual substitutes prepared drills for every contingency for actual understanding and the 767 and 777 manuals are afraid of spilling any corporate secrets.